For Workers

Workers’ portal by the Office as a Project, including workplace design research, personal workstation hacks & informational tools

Our Worker-Centred Resources Platform

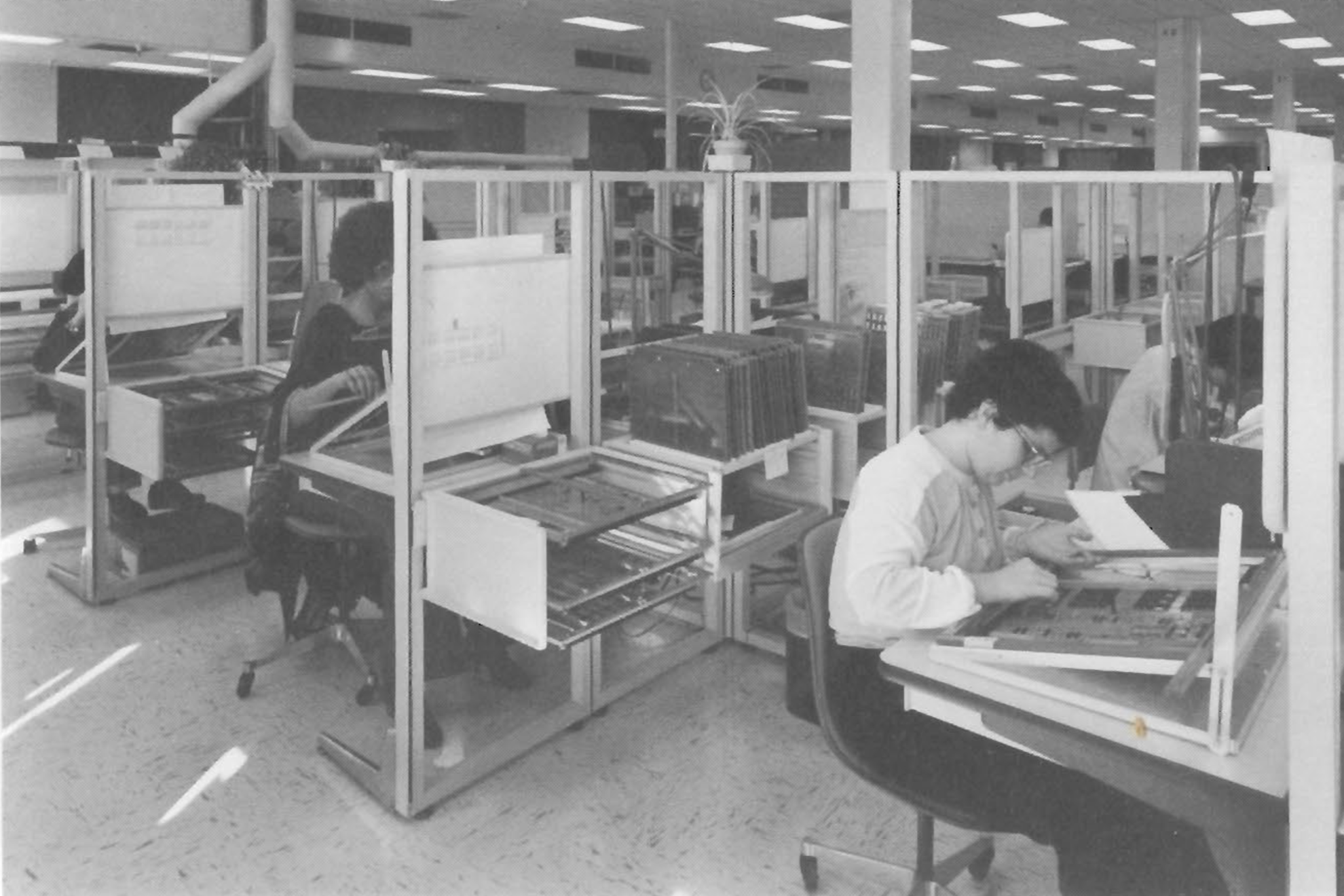

“Workspace that differentiate people on the basis of rank serve to communicate efficiently the hierarchy of influence in the organization:

‘[I]mmediately upon entering a work organization a stranger can readily place most of its members in their status position. He has countless cues by which he can judge their status.’ (Dubin, 1958, p. 38)

This is especially important for visitors from other organizations, who may need reassurance that they are dealing with the appropriate person...

Employees may react to egalitarian office by improvising their own unique status markers. In one office, where the furniture provided no means of distinguishing people, the employees developed a code:

‘The man with the red ashtray is a senior analyst. The man with the green ashtray is one of our programmers. The ones with two plants next to their desks are supervisors...’ (Zenardelli, 1967, p. 32)”

– Eric Sundstrom in “Work Places”, 1986

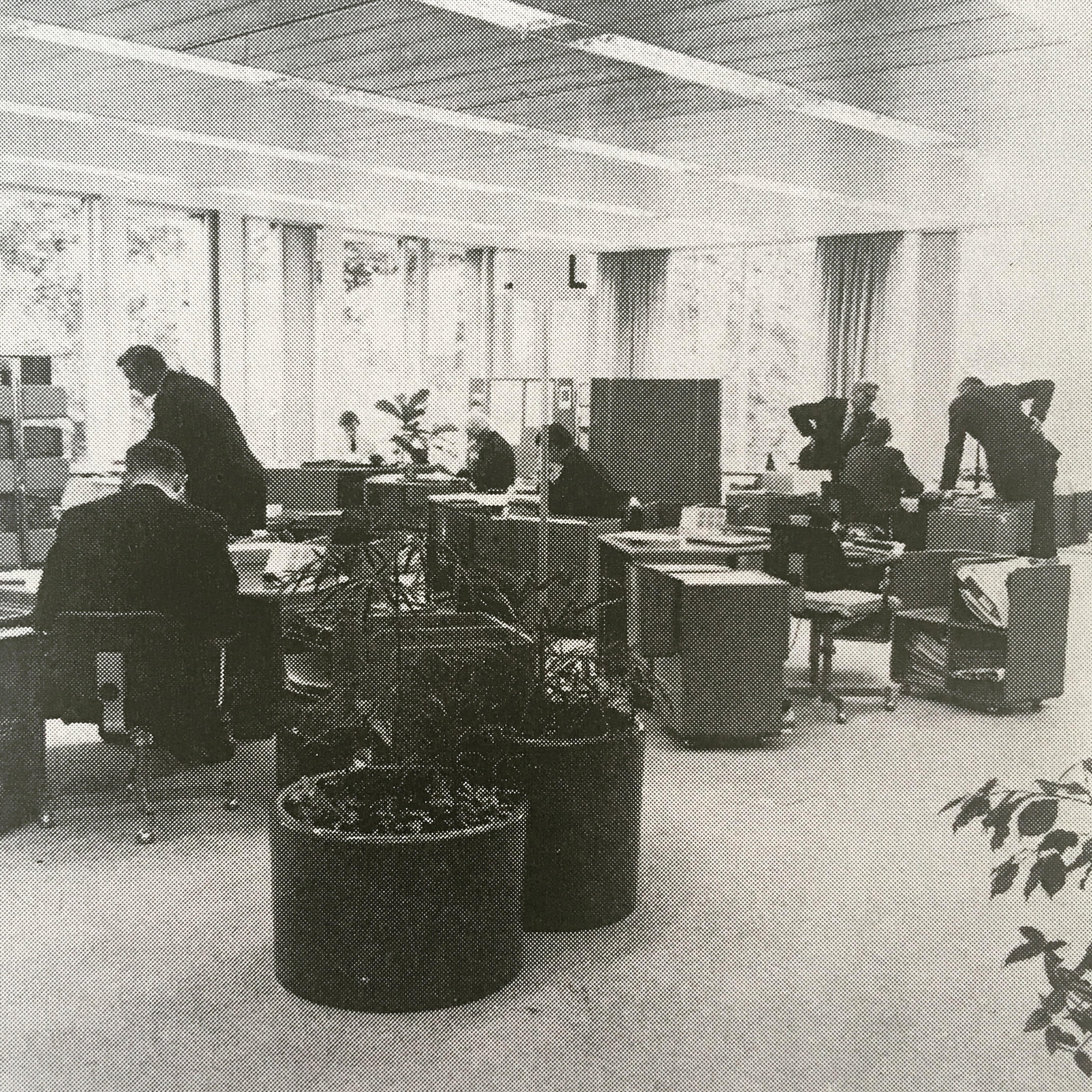

Photo:

An ‘egalitarian’ office in “Planning Office Space” by Duffy, Cave and Worthington, 1976

“Recasting all complex social situations either as neat problems with definite, computable solutions or as transparent and self-evident processes that can be easily optimized—if only the right algorithms are in place!—this quest is likely to have unexpected consequences that could eventually cause more damage than the problems they seek to address. I call the ideology that legitimizes and sanctions such aspirations "solutionism." I borrow this unabashedly pejorative term from the world of architecture and urban planning, where it has come to refer to an unhealthy preoccupation with sexy, monumental, and narrow-minded solutions—the kind of stuff that wows audiences at TED Conferences—to problems that are extremely complex, fluid, and contentious. These are the kinds of problems that, on careful examination, do not have to be defined in the singular and all-encompassing ways that "solutionists" have defined them; what's contentious, then, is not their proposed solution but their very definition of the problem itself…”

– Evgeny Morozov, from “To Save Everything, Click Here: The Folly of Technological Solutionism”, 2013

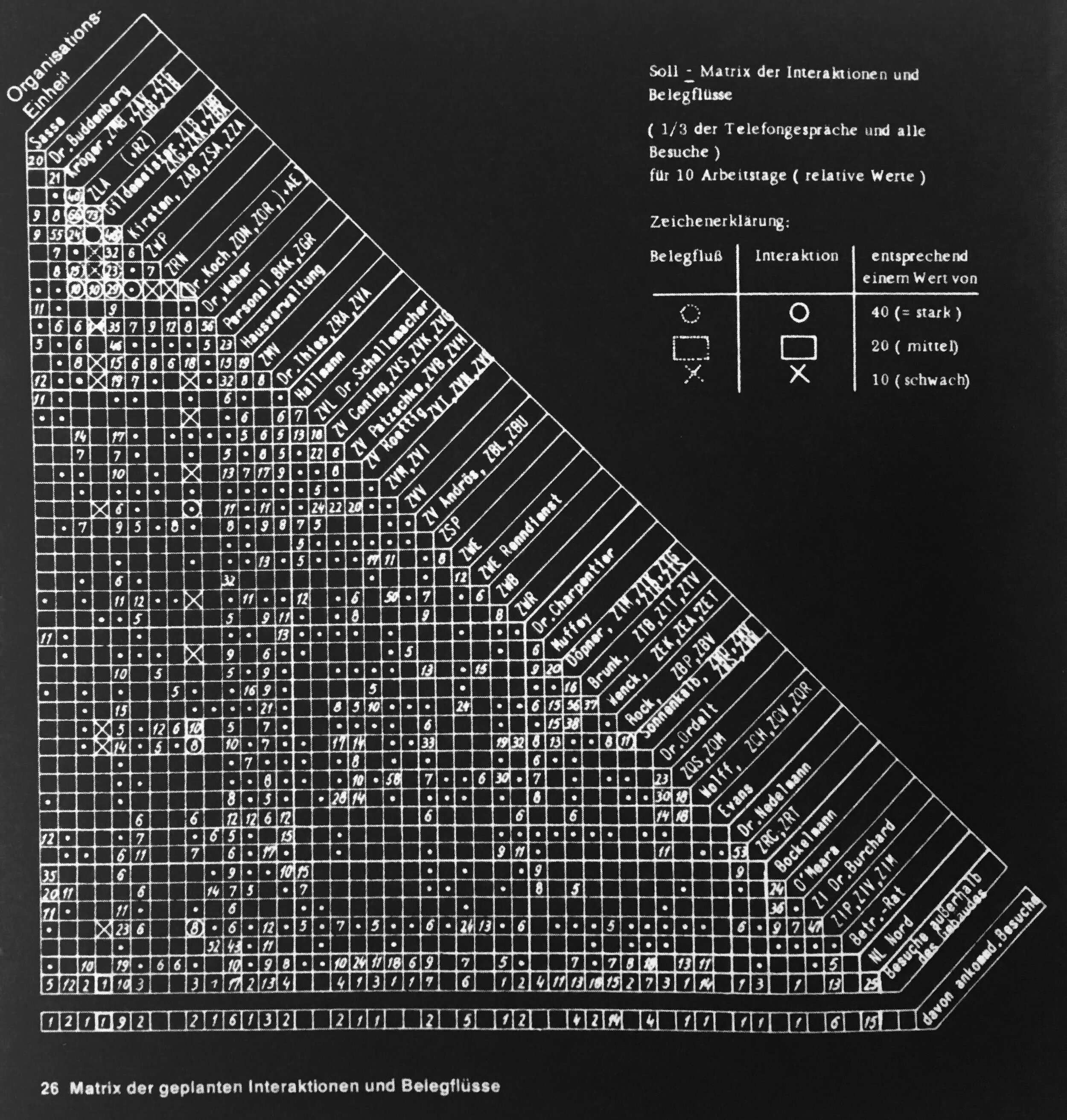

Photo:

Matrix of interactions within an organization, the Quickborner Team, ca. 1964, in “The Incorporation of Dissent: Bürolandschaft’s Legacy” by Andreas Rumpfhuber

“Flexibility is not the exhaustive anticipation of all possible changes. Most changes are unpredictable…Flexibility is the creation of a margin-excess capacity that enables different and even opposite interpretations and uses.”

– Rem Koolhaas, “Project for the Renovation of a Panopticon Prison”

Photo:

Superflexible Office, Konstantin Grcic for Vitra, Orgatec 2018

“The study remains, even in our houses today, a privileged space, a luxury in the midst of the practicalities of everyday life, a place to escape domesticity into a world of words and writing. The idea of the home office has brought the study back into the house but, at the same time, the ubiquity of the laptop and wi-fi and the diminution of the role and value of books has led to a dissolving of the room’s role into the dwelling as a whole. The study is the space of wisdom and learning, to lose it would be to delegate knowledge, to collapse the real space of inherited meaning and symbolism into the ether of cyberspace...”

– Edwin Heathcote, “Worlds of words,” Financial Times, 26 Sept 2009

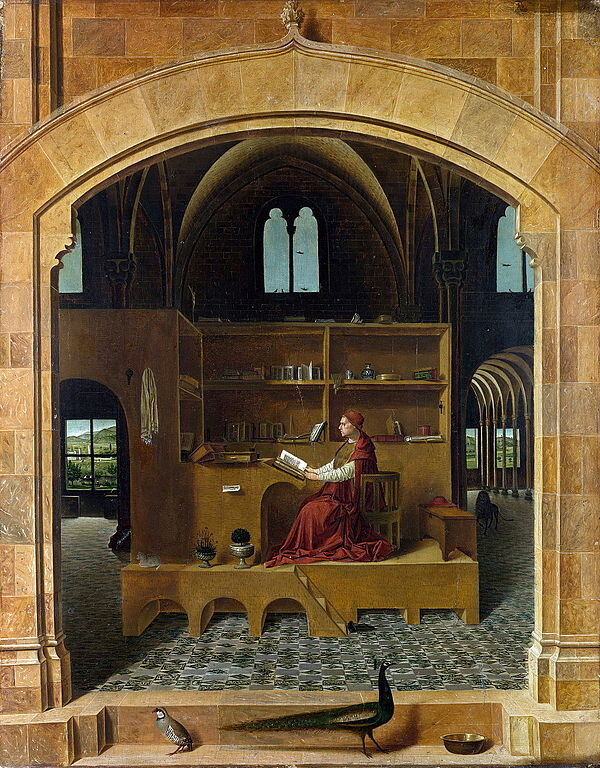

Photo:

“St. Jerome in His Study” by Antonello da Messina, c. 1474-5

“We typically assume that the more we can see, the more we can understand about an organization. This research suggests a counteracting force: the more that can be seen, the more individuals may respond strategically with hiding behavior and encryption to nullify the understanding of that which is seen. When boundaries to visibility fall, invisible boundaries to accurate understanding my replace them at a significant cost…”

– Ethan Bernstein in “The Transparency Paradox: A Role for Privacy in Organizational Learning and Operational Control”, Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 57, No. 2, 2012

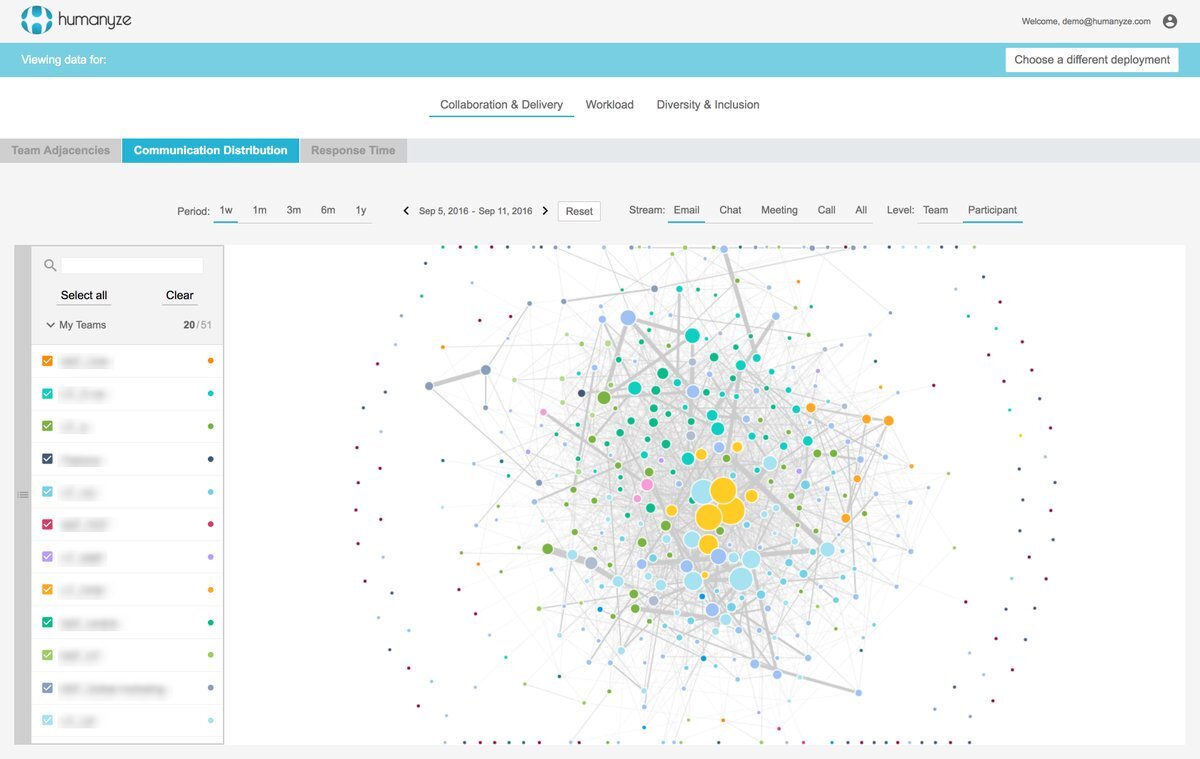

Photo:

Algorithmic analysis of formal and informal communication in the workplace, including email, chat, call and even face-to-face conversation through a wearable smart ID badge, by Humanyze. Graphics by Humanyze.com

“The formula [of the design office] quickly reveals itself: A waiting room and then a conference room give way to axes of semi-sequestered offices surrounding open work desks. But however open or flexible these workspaces might be, they aren’t very conducive to the unplanned interactions that generate ideas and fuel productivity, [Craig] Dykers says. “I can’t tell you how many meetings or presentations I’ve been to where everyone goes, ‘Well, this is great, but can we have a more informal meeting where we can maybe get some actual work done?’...

...Instead of relegating dining space to a Phantom of Liberty–like cloister, Dykers says, “we took it to extremes and really integrated this into the life of the studio.” He isn’t exaggerating—step out of the elevator and you walk right into the lunchroom. There is, in fact, no receptionist’s desk, only an array of long tables laid out before you. Whether guest or employee, you can’t enter without passing by them...

...The tables, depending on the hour, sprout varying topographies of models, renderings, charts, laptops, and foodstuffs. An orderly meal with uniform plates and cutlery punctuates the daily life of the Oslo tables; the American panoply of lunches spans a greater variety, from takeout to brown-bagged, and stretches across a longer span of hours... The lunchroom might be a place to blow off steam at points, but it’s also the capacious venue for ‘big, stressful meetings...’”

– Anthony Paletta in “Snøhetta Makes the Daily Lunch Break the Central Focus of Its Workplace”, Metropolis, Nov 10, 2015

Photo:

Snøhetta’s lunchroom in “Snøhetta Makes the Daily Lunch Break the Central Focus of Its Workplace”, Metropolis, Nov 10, 2015. Photos by Snøhetta

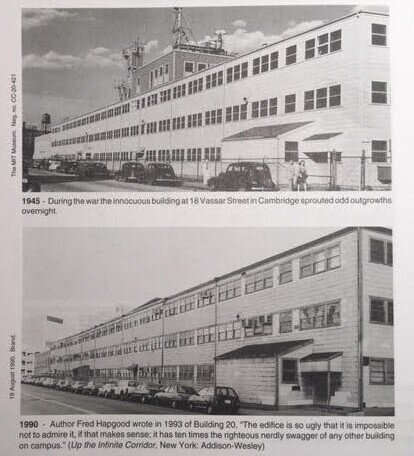

“The proposed new structure, known as Building 20, was going to be the biggest lab yet, comprising two hundred and fifty thousand square feet, on three floors. It was designed in an afternoon by a local architecture firm, and construction was quick and cheap. The design featured a wooden frame on top of a concrete-slab foundation, with an exterior covered in gray asbestos shingles. (Steel was in short supply.) The structure violated the Cambridge fire code, but it was granted an exemption because of its temporary status.

[But rather than a post-war demolition project, from 1946 onwards] Building 20 became a strange, chaotic domain, full of groups who had been thrown together by chance and who knew little about one another’s work. And yet, by the time it was finally demolished, in 1998, Building 20 had become a legend of innovation, widely regarded as one of the most creative spaces in the world…”

– “Groupthink: The brainstorming myth.” By Jonah Lehrer, in The New Yorker, Jan. 30, 2012 Issue

Photo:

MIT Building 20 by McCreery & Theriault, 1943, in “How Buildings Learn: What happens after they’re built” by Steward Brand, 1994

“In a piece for Harper’s in 1957, one labor official tasked with organizing white-collar workers plainly stated that his job was impossible and that unions trying to win them over, unless they changed tack completely, were doomed. The author—writing anonymously for fear of reprisal from his higher-ups—drew the conclusion that so many had refused to draw before but were now conceding: white-collar workers were different. They had clean jobs that didn’t force them to shower when they came home each day. They believed ardently in the American dream of relentless upward mobility. They preferred the insecurity of getting promoted based on merit to the steady advance of seniority. Unions promised one thing above all—dignity—which white-collar workers claimed they already had…”

– Nikil Saval, “Cubed: A Secret History of the Workplace”, 2014

Photo:

Cover of “White-Collar Unionism” by K. Prandy, A. Stewart & R. M. BlackBurn, 1983

“In many ways the East India Company was a model of corporate efficiency: 100 years into its history, it had only 35 permanent employees in its head office. Nevertheless, that skeleton staff executed a corporate coup unparalleled in history: the military conquest, subjugation and plunder of vast tracts of southern Asia…[It] no longer exists, and it has, thankfully, no exact modern equivalent….yet the EIC – the first great multinational corporation, and the first to run amok – was the ultimate model for many of today’s joint-stock corporations.”

– William Dalrymple in “The East India Company: The original corporate raiders” in The Guardian, March 4, 2015

Photo:

“The Mughal emperor Shah Alam hands a scroll to Robert Clive, the governor of Bengal, which transferred tax collecting rights in Bengal, Bihar and Orissa to the East India Company.” By Benjamin West, 1738–1820

During the course of the 20th century, some combination of mass production, mail order catalogues, the rise in corporate administration and Modernist design sensibilities facilitated an evolution of the ‘desk’ into the ‘workstation’. And if Robert Propst’s Action Office is the oft-cited emblem of this shift, then perhaps George Nelson’s 1946 “Home Office Desk” is the missing link. Compare this relatively utilitarian design, created quietly under the auspices of the then-named Miller Furniture Company for their very first catalogue, with the expressive, bespoke writing desks of Frank Lloyd Wright for his total work at Johnson Wax a decade before...

Photo:

Home Office Desk, George Nelson Associates for Miller Furniture Company, 1943 / Writing Desk for Johnson Wax Headquarters, Wisconsin, USA, 1939, Photo by Bill Zbaren

Photo:

Chronocyclograph from Time Motion Studies by Frank and Lillian Gilbreth, ca 1910-1924

The common elements of modern office chairs—e.g. a swivel, casters and some consideration of ergonomics—make an earlier appearance in the design of workplace seating than one might immediately assume. Debuted at The Great Exhibition in London of 1851, Thomas E. Warren’s “Centripetal Spring Chair” had all the characteristics of a modern task chair (allowing for movement, rotation and even seat angle adjustment) albeit obsessively hidden behind elaborate ornament and trim—a choice that curiously seems to betray a degree of self-consciousness concerning the true novelty of the design…

Photo:

“Centripetal Spring Chair”, Thomas E. Warren, ca. 1849-1858, photos by the Brooklyn Museum

The common elements of modern office chairs—e.g. a swivel, casters and some consideration of ergonomics—make an earlier appearance in the design of workplace seating than one might immediately assume. Debuted at The Great Exhibition in London of 1851, Thomas E. Warren’s “Centripetal Spring Chair” had all the characteristics of a modern task chair (allowing for movement, rotation and even seat angle adjustment) albeit obsessively hidden behind elaborate ornament and trim—a choice that curiously seems to betray a degree of self-consciousness concerning the true novelty of the design…

Photo:

“Centripetal Spring Chair”, Thomas E. Warren, ca. 1849-1858, photos by the Brooklyn Museum

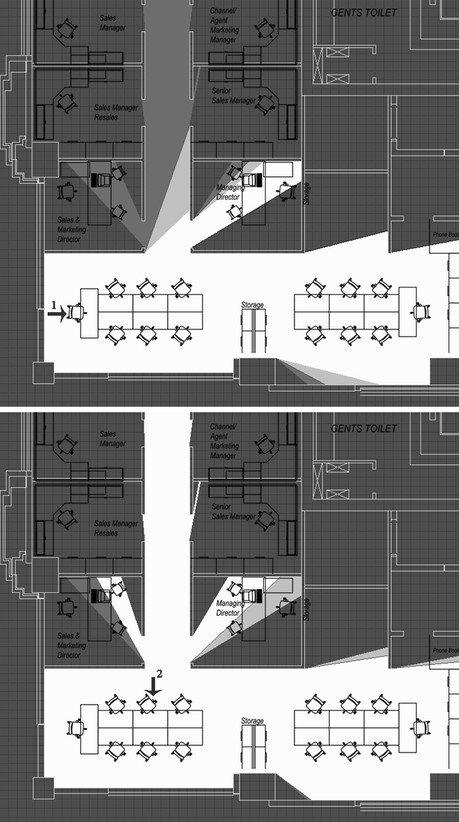

“Radicalism problematizes control around the need to coerce employees into doing something they would otherwise not do—that is, to work as hard as they can all the time, even though such hard work is not obviously in their own interests. Thus, organizational surveillance of the few watching the many is justified, because it enables a small number of managers to exercise control over a larger and potentially unruly mass of employees through the monitoring of individual behaviour.

In contrast to the radical tradition, liberalism considers social control to be legitimate as long as (1) on balance, it promotes greater liberty, (2) it is implemented by impartial experts, and (3) it ensures that all citizens meet their mutual obligations under some form of social contract. Intrusive measures, including the surveillance of the many by the few, that prevent socially unacceptable behavior are tolerable as long as the above conditions are satisfied and the normal checks and balances of the liberal democratic state are observed...”

– Graham Sewell and James R. Barker, “Coercion versus Care: Using Irony to Make Sense of Organizational Surveillance”, The Academy of Management Review, Vol. 31, No. 4, Oct 2006

Photo:

Visible space analysis (isovists) from various desk positions by Linda N. Nubani, “Evaluating Workplace Constructs Using Computerized Techniques of Space Syntax”, Building Performance Evaluation, Aug 31 2017

“the computer is no longer a mysterious giant working away in the hidden recesses of large organizations, but rather is a highly functional and friendly device that almost anyone can use almost anywhere there’s work to be done.”

– in Hewlett-Packard’s internal magazine, ‘Measure’, Feb 1979

The initiative started with the development of a desktop computer system, the HP 300 ‘Amigo’. Their desire was to make their product as compatible as possible with modern office design, reaching out to Herman Miller and teaming up with Action Office, partly as a marketing strategy.

But as they began working together on product development, they started looking at the manufacturing process itself—at issues like the flow of materials, unnecessary parts damage, inefficient space utilization, waste, and excessive manual material handling. This eventually led to the creation of a streamlined system of walls, surfaces, containers, and conveyances that “resembled an office for factory workers more than a factory in the traditional sense.” And, correspondingly, because HP product designers were involved throughout, the 300 was also a rare example of the production process of a product informing the design of the product itself…

Photo:

Action Factory, ca. 1979

A selection of original research documenting lesser-known aspects of workplace design & workplace design thinking.